"Portentous," "monumental," "damn near endless" are all descriptions that came to mind after seeing Apocalypse Now (1979; dir. Francis Ford Coppola). The Paris Theater’s "Big and Loud" series presented the restoration of the original roadshow version, which runs just shy of three hours. When the film ended, without credits, it felt like I’d been hit repeatedly about the head and shoulders with a heavy, blunt instrument, and I don’t mean that as a compliment. There’s a lot to take in, and it takes time and reflection to make sense of the movie.After seeing Megadoc, Mike Figgis’ documentary charting the making of Coppola’s most recent feature, Megalopolis, just the other day, I can see parallels between the two movies, despite their being made more than 40 years apart. From the evidence of the two movies, I’d say that Coppola is more interested in big themes than simple stories; in an epic scope rather than human scale; and in spotlighting operatic violence, even buckets of blood, whenever possible. He strives to reach 11 on a scale of 10, and succeeds more often than not, leaving the audience gasping in his wake. I believe the Sicilian word is stonnat' or stunned.

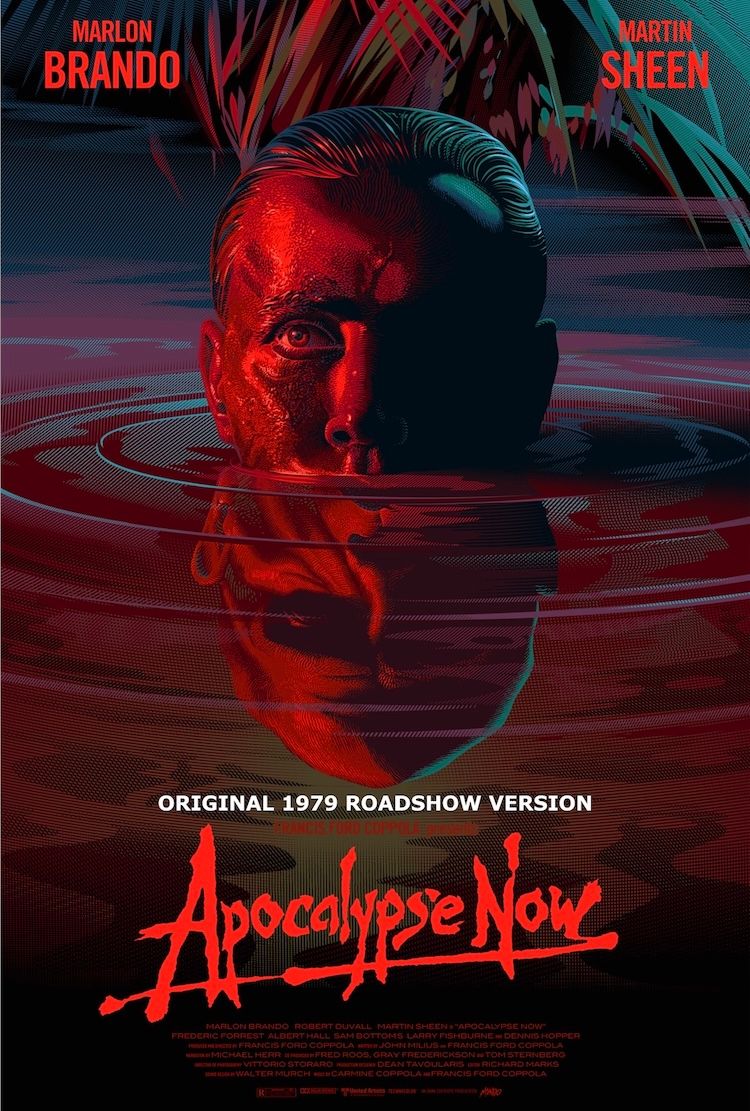

To recap the plot, Apocalypse Now takes place during the Vietnam War and is about Captain Willard (Martin Sheen), who is sent up the Nung River to find Colonel Kurtz (Marlon Brando), a renegade Green Beret who’s conducting a private war from a base in Cambodia. Along the way, Willard witnesses and participates in a string of horrific war crimes that do nothing to advance the plot, but pretty effectively traumatize the audience much as the war traumatized the soldiers who fought in it. Finally, he finds Kurtz’s base and at that point the movie turns into a dramatization of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, which was set in the Belgian Congo at the time of King Leopold’s worst atrocities. Not only is Kurtz certifiably insane, but a photographer (Dennis Hopper) is loose on the property and he’s floridly psychotic as only Hopper can be. Kurtz takes Willard prisoner, tortures him, then frees him, and (no spoilers) Willard has to decide if he’s going to carry out his mission. In the meantime, an ox is ritually slaughtered, serving as an on-the-nose metaphor and yet another spectacular set piece.

Coppola made Apocalypse Now, at considerable personal cost, to put the war on the screen. It was his answer to the question posed in Norman Mailer’s book Why Are We in Vietnam?, and unlike Mailer, whose answer was that the war was sublimated homosexual dominance on a grand scale, Coppola showed what the war looked like and how it destroyed the people who were sent to fight it. Tens of thousands were killed, the rest were traumatized.

The problem for me after my first viewing was that beyond showing how Captain Willard, who starts out pretty unhinged (he bloodies his fist by punching a mirror in a drunken stupor in the movie's first 10 minutes), ends up nearly catatonic after he leaves Kurtz’s compound, it seemed like there wasn’t anything else to take away about the characters. With some reflection, I changed my mind.

Willard starts out damaged and ends up wrecked by what he’s been through and what he’s had to do. The surfer, Lance (Sam Bottoms, Timothy Bottoms’ brother), is similarly wrecked, though his LSD trips shield him from the worst of the carnage he’s witnessed and participated in. And the audience should be touched in a similar way, though some people may remember the visuals more clearly than the message. This isn’t surprising, since Coppola’s message is widely understood today, more than when the film was released.

For many viewers, the spectacle is enough—the helicopter ballet to Wagner’s Ride of the Valkyries gave me goosebumps, the explosions were lovely, and Kurtz’s compound in a Cambodian ruin was beautiful. That Apocalypse Now is more than this, that Captain Willard becomes an empty shell to cope with his experience inside the heart of darkness, is a testament to John Milius’ script and Coppola’s vision as a director.